Charlotte Ruhl, a psychology graduate from Harvard College, boasts over six years of research experience in clinical and social psychology. During her tenure at Harvard, she contributed to the Decision Science Lab, administering numerous studies in behavioral economics and social psychology.

Reviewed by

&Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

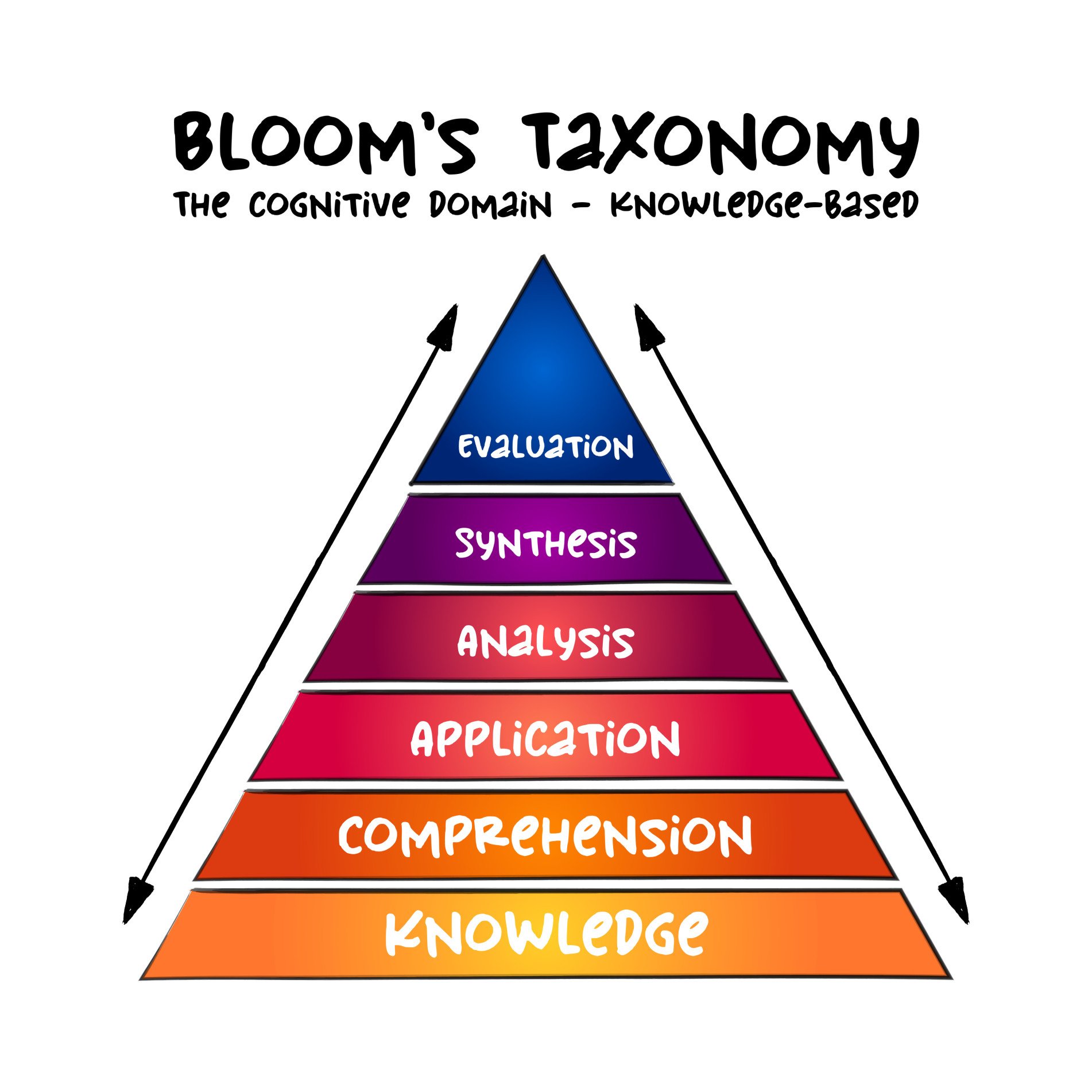

Bloom’s Taxonomy is a set of three hierarchical models used to classify educational learning objectives into levels of complexity and specificity. The three lists cover the learning objectives in cognitive, affective, and sensory domains, namely: thinking skills, emotional responses, and physical skills.

Take a moment and think back to your 7th-grade humanities classroom. Or any classroom from preschool to college. As you enter the room, you glance at the whiteboard to see the class objectives.

“Students will be able to…” is written in a red expo marker. Or maybe something like “by the end of the class, you will be able to…” These learning objectives we are exposed to daily are a product of Bloom’s Taxonomy.

Bloom’s Taxonomy is a system of hierarchical models (arranged in a rank, with some elements at the bottom and some at the top) used to categorize learning objectives into varying levels of complexity (Bloom, 1956).

You might have heard the word “taxonomy” in biology class before, because it is most commonly used to denote the classification of living things from kingdom to species.

In the same way, this taxonomy classifies organisms, Bloom’s Taxonomy classifies learning objectives for students, from recalling facts to producing new and original work.

Bloom’s Taxonomy comprises three learning domains: cognitive, affective, and psychomotor. Within each domain, learning can take place at a number of levels ranging from simple to complex.

Benjamin Bloom was an educational psychologist and the chair of the committee of educators at the University of Chicago.

In the mid 1950s, Benjamin Bloom worked in collaboration with Max Englehart, Edward Furst, Walter Hill, and David Krathwohl to devise a system that classified levels of cognitive functioning and provided a sense of structure for the various mental processes we experience (Armstrong, 2010).

Through conducting a series of studies that focused on student achievement, the team was able to isolate certain factors both inside and outside the school environment that affect how children learn.

One such factor was the lack of variation in teaching. In other words, teachers were not meeting each individual student’s needs and instead relied upon one universal curriculum.

To address this, Bloom and his colleagues postulated that if teachers were to provide individualized educational plans, students would learn significantly better.

This hypothesis inspired the development of Bloom’s Mastery Learning procedure in which teachers would organize specific skills and concepts into week-long units.

The completion of each unit would be followed by an assessment through which the student would reflect upon what they learned.

The assessment would identify areas in which the student needs additional support, and they would then be given corrective activities to further sharpen their mastery of the concept (Bloom, 1971).

This theory that students would be able to master subjects when teachers relied upon suitable learning conditions and clear learning objectives was guided by Bloom’s Taxonomy.

Bloom’s Taxonomy was originally published in 1956 in a paper titled Taxonomy of Educational Objectives (Bloom, 1956).

The taxonomy provides different levels of learning objectives, divided by complexity. Only after a student masters one level of learning goals, through formative assessments, corrective activities, and other enrichment exercises, can they move onto the next level (Guskey, 2005).

The original version of the taxonomy, the cognitive domain, is the first and most common hierarchy of learning objectives (Bloom, 1956). It focuses on acquiring and applying knowledge and is widely used in the educational setting.

This initial cognitive model relies on nouns, or more passive words, to illustrate the different educational benchmarks.

Because it is hierarchical, the higher levels of the pyramid are dependent on having achieved the skills of the lower levels.

The individual tiers of the cognitive model from bottom to top, with examples included, are as follows:

Although knowledge might be the most intuitive block of the cognitive model pyramid, this dimension is actually broken down into four different types of knowledge:

However, this is not to say that this order reflects how concrete or abstract these forms of knowledge are (e.g., procedural knowledge is not always more abstract than conceptual knowledge).

Nevertheless, it is important to outline these different forms of knowledge to show how it is more dynamic than one may think and that there are multiple different types of knowledge that can be recalled before moving onto the comprehension phase.

And while the original 1956 taxonomy focused solely on a cognitive model of learning that can be applied in the classroom, an affective model of learning was published in 1964 and a psychomotor model in the 1970s.

The affective model came as a second handbook (with the first being the cognitive model) and an extension of Bloom’s original work (Krathwol et al., 1964).

This domain focuses on the ways in which we handle all things related to emotions, such as feelings, values, appreciation, enthusiasm, motivations, and attitudes (Clark, 2015).

From lowest to highest, with examples included, the five levels are:

The psychomotor domain of Bloom’s Taxonomy refers to the ability to physically manipulate a tool or instrument. It includes physical movement, coordination, and use of the motor-skill areas. It focuses on the development of skills and the mastery of physical and manual tasks.

Mastery of these specific skills is marked by speed, precision, and distance. These psychomotor skills range from simple tasks, such as washing a car, to more complex tasks, such as operating intricate technological equipment.

As with the cognitive domain, the psychomotor model does not come without modifications. This model was first published by Robert Armstrong and colleagues in 1970 and included five levels:

1) imitation; 2) manipulation; 3) precision; 4) articulation; 5) naturalization. These tiers represent different degrees of performing a skill from exposure to mastery.

Two years later, Anita Harrow (1972) proposed a revised version with six levels:

1) reflex movements; 2) fundamental movements; 3) perceptual abilities; 4) physical abilities; 5) skilled movements; 6) non-discursive communication.

This model is concerned with developing physical fitness, dexterity, agility, and body control and focuses on varying degrees of coordination, from reflexes to highly expressive movements.

That same year, Elizabeth Simpson (1972) created a taxonomy that progressed from observation to invention.

The seven tiers, along with examples, are listed below:

In 2001, the original cognitive model was modified by educational psychologists David Krathwol (with whom Bloom worked on the initial taxonomy) and Lorin Anderson (a previous student of Bloom) and published with the title A Taxonomy for Teaching, Learning, and Assessment .

This revised taxonomy emphasizes a more dynamic approach to education instead of shoehorning educational objectives into fixed, unchanging spaces.

To reflect this active model of learning, the revised version utilizes verbs to describe the active process of learning and does away with the nouns used in the original version (Armstrong, 2001).

The figure below illustrates what words were changed and a slight adjustment to the hierarchy itself (evaluation and synthesis were swapped). The cognitive, affective, and psychomotor models make up Bloom’s Taxonomy.

Thanks to Bloom’s Taxonomy, teachers nationwide have a tool to guide the development of assignments, assessments, and overall curricula.

This model helps teachers identify the key learning objectives they want a student to achieve for each unit because it succinctly details the learning process.

This hierarchy takes students through a process of synthesizing information that allows them to think critically. Students start with a piece of information and are motivated to ask questions and seek out answers.

Not only does Bloom’s Taxonomy help teachers understand the process of learning, but it also provides more concrete guidance on how to create effective learning objectives.

| Bloom’s Level | Key Verbs (keywords) | Example Learning Objective |

|---|---|---|

| Create | design, formulate, build, invent, create, compose, generate, derive, modify, develop. | By the end of this lesson, the student will be able to design an original homework problem dealing with the principle of conservation of energy. |

| Evaluate | choose, support, relate, determine, defend, judge, grade, compare, contrast, argue, justify, support, convince, select, evaluate. | By the end of this lesson, the student will be able to determine whether using conservation of energy or conservation of momentum would be more appropriate for solving a dynamics problem. |

| Analyze | classify, break down, categorize, analyze, diagram, illustrate, criticize, simplify, associate. | By the end of this lesson, the student will be able to differentiate between potential and kinetic energy. |

| Apply | calculate, predict, apply, solve, illustrate, use, demonstrate, determine, model, perform, present. | By the end of this lesson, the student will be able to calculate the kinetic energy of a projectile. |

| Understand | describe, explain, paraphrase, restate, give original examples of, summarize, contrast, interpret, discuss. | By the end of this lesson, the student will be able to describe Newton’s three laws of motion in her/his own words |

| Remember | list, recite, outline, define, name, match, quote, recall, identify, label, recognize. | By the end of this lesson, the student will be able to recite Newton’s three laws of motion. |

The revised version reminds teachers that learning is an active process, stressing the importance of including measurable verbs in the objectives.

And the clear structure of the taxonomy itself emphasizes the importance of keeping learning objectives clear and concise as opposed to vague and abstract (Shabatura, 2013).

Bloom’s Taxonomy even applies at the broader course level. That is, in addition to being applied to specific classroom units, Bloom’s Taxonomy can be applied to an entire course to determine the learning goals of that course.

Specifically, lower-level introductory courses, typically geared towards freshmen, will target Bloom’s lower-order skills as students build foundational knowledge.

However, that is not to say that this is the only level incorporated, but you might only move a couple of rungs up the ladder into the applying and analyzing stages.

On the other hand, upper-level classes don’t emphasize remembering and understanding, as students in these courses have already mastered these skills.

As a result, these courses focus instead on higher-order learning objectives such as evaluating and creating (Shabatura, 2013). In this way, professors can reflect upon what type of course they are teaching and refer to Bloom’s Taxonomy to determine what they want the overall learning objectives of the course to be.

Having these clear and organized objectives allows teachers to plan and deliver appropriate instruction, design valid tasks and assessments, and ensure that such instruction and assessment actually aligns with the outlined objectives (Armstrong, 2010).

Overall, Bloom’s Taxonomy helps teachers teach and helps students learn!

Bloom’s Taxonomy accomplishes the seemingly daunting task of taking the important and complex topic of thinking and giving it a concrete structure.

The taxonomy continues to provide teachers and educators with a framework for guiding the way they set learning goals for students and how they design their curriculum.

And by having specific questions or general assignments that align with Bloom’s principles, students are encouraged to engage in higher-order thinking.

However, even though it is still used today, this taxonomy does not come without its flaws. As mentioned before, the initial 1956 taxonomy presented learning as a static concept.

Although this was ultimately addressed by the 2001 revised version that included active verbs to emphasize the dynamic nature of learning, Bloom’s updated structure is still met with multiple criticisms.

Many psychologists take issue with the pyramid nature of the taxonomy. The shape creates the false impression that these cognitive steps are discrete and must be performed independently of one another (Anderson & Krathwol, 2001).

However, most tasks require several cognitive skills to work in tandem with each other. In other words, a task will not be only an analysis or a comprehension task. Rather, they occur simultaneously as opposed to sequentially.

The structure also makes it seem like some of these skills are more difficult and important than others. However, adopting this mindset causes less emphasis on knowledge and comprehension, which are as, if not more important, than the processes towards the top of the pyramid.

Additionally, author Doug Lemov (2017) argues that this contributes to a national trend devaluing knowledge’s importance. He goes even further to say that lower-income students who have less exposure to sources of information suffer from a knowledge gap in schools.

A third problem with the taxonomy is that the sheer order of elements is inaccurate. When we learn, we don’t always start with remembering and then move on to comprehension and creating something new. Instead, we mostly learn by applying and creating.

For example, you don’t know how to write an essay until you do it. And you might not know how to speak Spanish until you actually do it (Berger, 2020).

The act of doing is where the learning lies, as opposed to moving through a regimented, linear process. Despite these several valid criticisms of Bloom’s Taxonomy, this model is still widely used today.

Bloom’s Taxonomy is a hierarchical model of cognitive skills in education, developed by Benjamin Bloom in 1956.

It categorizes learning objectives into six levels, from simpler to more complex: remembering, understanding, applying, analyzing, evaluating, and creating. This framework aids educators in creating comprehensive learning goals and assessments.

Bloom’s Taxonomy is a framework that helps you understand and approach learning in a structured way. Imagine it as a ladder with six steps.

1. Remembering: This is the first step, where you learn to recall or recognize facts and basic concepts.

2. Understanding: You explain ideas or concepts and make sense of the information.

3. Applying: You apply what you’ve understood to solve problems in new situations.

4. Analyzing: At this step, you break information into parts to explore understandings and relationships.

5. Evaluating: This involves judging the value of ideas or materials.

6. Creating: This is the top step where you combine information to form a new whole or propose alternative solutions.

Bloom’s Taxonomy helps you learn more effectively by building your knowledge from simple remembering to higher levels of thinking.

Anderson, L. W., Krathwohl, D. R. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. New York: Longman.

Armstrong, P. (2010). Bloom’s Taxonomy. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Retrieved from https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/blooms-taxonomy/

Armstrong, R. J. (1970). Developing and Writing Behavioral Objectives.

Berger, R. (2020). Here’s what’s wrong with bloom’s taxonomy: A deeper learning perspective (opinion). Retrieved from https://www.edweek.org/education/opinion-heres-whats-wrong-with-blooms-taxonomy-a-deeper-learning-perspective/2018/03

Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives. Vol. 1: Cognitive domain. New York: McKay, 20, 24.

Bloom, B. S. (1971). Mastery learning. In J. H. Block (Ed.), Mastery learning: Theory and practice (pp. 47–63). New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Clark, D. (2015). Bloom’s taxonomy: The affective domain. Retrieved from http://www.nwlink.com/~donclark/hrd/Bloom/affective_domain.html

Guskey, T. R. (2005). Formative Classroom Assessment and Benjamin S. Bloom: Theory, Research, and Implications. Online Submission.

Harrow, A.J. (1972). A taxonomy of the psychomotor domain. New York: David McKay Co.

Krathwohl, D. R. (2002). A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy: An overview. Theory into practice, 41 (4), 212-218.

Krathwohl, D.R., Bloom, B.S., & Masia, B.B. (1964). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook II: Affective domain. New York: David McKay Co.

Lemov, D. (2017). Bloom’s taxonomy-that pyramid is a problem. Retrieved from https://teachlikeachampion.com/blog/blooms-taxonomy-pyramid-problem/

Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.celt.iastate.edu/teaching/effective-teaching-practices/revised-blooms-taxonomy/

Shabatura, J. (2013). Using bloom’s taxonomy to write effective learning objectives. Retrieved from https://tips.uark.edu/using-blooms-taxonomy/

Simpson, E. J. (1972). The classification of educational objectives in the Psychomotor domain, Illinois University. Urbana.